Setting a High Bar for Poverty in India

NEW DELHI — It is not uncommon for Indians to stand in a line to receive alms from a politician as he gives away clothes, pots and laptops that would make Apple laugh. This is a custom that has survived from a time when the theater of charity was enough to make the poor feel grateful. But they have since come to regard such alms as political buffoonery and now expect substantial assistance from the government.

To bring order to the public spending that subsidizes hundreds of millions of lives, and to ensure that the poorest receive what is meant for them, India is on a constant quest for a meaningful definition of poverty. The latest recommendation is from a committee headed by a former chairman of the prime minister’s Economic Advisory Council, Chakravarthi Rangarajan. Under the recommendation, a rural family of five spending less than 4,860 rupees, or about $80, a month, or an urban family spending less than 7,035 rupees, at 2011-12 prices, should be deemed poor. This marks 363 million Indians, or 29.5 percent, as poor in 2011-12, the latest period analyzed by committee.

No definition of poverty in India has ever had such a high bar, yet when applied over the years it shows the percentage of Indians living in abject poverty as falling. In 2010, according to the committee, 38.2 percent of Indians were poor.

The committee studied government statistics to ascertain the ability of households to pay for food that provides the minimum nutrition a human needs to function normally, including 48 to 50 grams of protein per person per day, and on education, health care, housing and a range of products including electricity, transport and clothing.

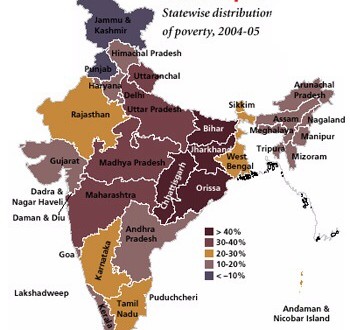

The committee’s report also points to how wildly prices of goods vary across India. The most expensive regions for the poor are about twice as costly as the cheapest.

When the recently elected prime minister, Narendra Modi, was campaigning against the governing Indian National Congress party, he frequently bragged about the way he ran the state of Gujarat as its chief minister since 2001. While Gujarat’s per capita income is among India’s highest, the fact is that its poverty rate in 2011-12, at 27.4 percent, was only a shade below the national average, according to the committee’s report. Its rural poverty rate, at 31.4 percent, was higher than the national average.

These figures are not startling revelations. They reconfirm what the economist Amartya Sen loathes about Gujarat’s economic model — that its preoccupation with industrialization and disdain for welfare programs have created huge income inequalities. Its poor are so poor that they are unable to exploit the economic opportunities as efficiently as the more fortunate.

The southern state of Kerala, which Mr. Sen admires, is a horror for those who want to start industries, but it has almost-First World social indicators, thanks to its tradition of investing heavily in social welfare. Kerala’s poverty rate in 2011-12 was 11.3 percent, according to committee, with only 7.3 percent of its rural population poor.

Much of Kerala’s wealth comes not from within, but from a work force spread across the country and the rest of the world, chiefly in Middle Eastern nations. But the fact is that, because Kerala has invested in education and health care, it has ensured that a large proportion of its population, and not just its elite, could pounce on opportunities wherever they sprang up.

The last time India defined poverty, about three years ago, the rich laughed, partly because they liked to laugh at everything the Congress party did. They said the poverty line was set too low.

Some agitated people, misled by the arithmetic of dividing household expenditure by family members, wondered how anyone could survive on about 33 rupees a day. Several daft politicians set out to prove one could.

There is no such outrage over Mr. Rangarajan’s recommendations. Now that its archvillain, the Congress party, has been slain, the middle class appears less agitated by matters like poverty lines.

Manu Joseph is author of the novel “The Illicit Happiness of Other People.”